The Real "Auntie Mame"

Photo © The Shubert Organization

Photo © Pictorial Parade.

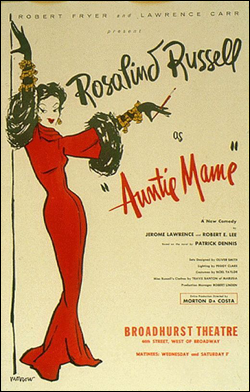

In the hit Broadway play "Auntie Mame," Mame Dennis, a zany Bohemian whose motto is "Life is a banquet and most poor sons-of-bitches are starving to death," is enjoying a hedonistic life when she unexpectedly becomes ward to her nephew, Patrick. Mame has to decide whether to give Patrick a traditional upbringing, or take him along on her adventures. She chooses the latter, and “Auntie Mame” is their story.

“Auntie Mame” was based on the novel of the same name by Edward Everett Tanner 3d, who wrote under the pen name Patrick Dennis (the same name as Mame’s nephew in the play). Tanner said that his book was based on his aunt, a real-life bon vivant and eccentric named Marion Tanner.

In the late 1920s (the same period covered in the play), Marion used her Greenwich Village townhouse as an impromptu salon for artists, painters, writers, and philosophers (“Bohemian types,” she called them in an interview). In addition, she took in and cared for homeless children, which may have given Edward the idea to imagine what life would be like for a child under her care.

Is Marion Tanner Auntie Mame?

Photo © Vernon Shibla/NYP Holdings

The question of how much of Auntie Mame is based on Marion Tanner has been the subject of speculation for years. That’s partly because both Tanners initially said Marion was the model for Mame, but after the two had a falling-out (see below), Edward denied the link. He also let Marion know that he was annoyed that she kept referring to herself as “the real Auntie Mame.” (At one point, she parlayed that distinction into a guest spot on a game show, where she won $20,000.)

In interviews, Edward stated that his novel wasn’t autobiographical, and that he had known many eccentric women who influenced his work. Nevertheless, there are parallels between the fictional and real characters:

- Mame was born in Buffalo, New York, attended Smith College, worked at Macy's, had a part in a play, hosted an artist’s salon on Beekman Place, and established a home for refugees.

- Marion Tanner was born in Buffalo and went to Smith, too. She also worked at Macy's, appeared in several plays, played host to artists, and cared for homeless children.

Photo © Google Maps

But in other ways, Marion Tanner was very different. Eric Myers, who wrote Edward Tanner's biography, Uncle Mame, described Marion as “dowdy” and “straggly-haired,” saying she was “more evocative of a bag lady than anyone’s idea of Auntie Mame.” And a Bank St. neighbor who knew Marion in her early 70s described her as “short and wrinkled, with missing teeth and thinning gray hair tucked into a bun.”

Perhaps Edward Tanner’s wife, Louise, had it right: She held that Marion Tanner provided just the kernel for the character of Auntie Mame. Her husband was, by then, a successful novelist who knew how to exaggerate a character’s idiosyncracies for comic effect.

Marion's Later Years

After the artists and bon vivants left Marion's townhouse, the nature of her guests changed. In the early 1960s, she opened her home to just about anyone she felt was less fortunate than herself (she reportedly had the lock removed from her front door). It became a flophouse for people “all too eager to take advantage of Marion’s blind generosity,” according to an acquaintance. That included street people, drunks, and drug addicts. A neighbor who grew up across the street from Marion used to visit her house as a young girl and recalled seeing visitors, “many of whom had seen better days, stream in and out.” And a friend of Marion’s, Frank Andrews, described her house during this period: “The place was a shambles; it reeked of urine. Little kids were running around. They would just pee on the walls. She was into yoga, and she’d be off in a corner doing meditation.…”

Edward Tanner tried to convince his aunt to stop taking in strangers, and to sell her house (she was single and in her 70s by then). He also told her that he objected to her using his support money to feed and house these "visitors."

Photo © Google Maps.

Marion's house was sold, and a friend invited her to live and work at Bierer House, a halfway house for emotionally troubled people in neighboring Chelsea. The tenants at Bierer loved her, and she stayed for 13 years. In 1977, as she deteriorated physically and mentally, she moved to the Village Nursing Home, just down the street from her old Bank St. home.

In 1976, Edward Tanner died of pancreatic cancer at age 55, never having reconciled with his aunt.

In 1985, two months after suffering a stroke, Marion caught pneumonia and died at age 94 on October 31st—29 years to the day after “Auntie Mame” opened on Broadway.

The people Marion helped remembered her kindness and love of life. “I met her in February 30 years ago, in the basement of 72 Bank St.,” said Graham McKeen, a composer. “I was sick, drunk. She got me to St. Vincent's Hospital. She saved my life. She never preached to me. She just kept saying: 'Keep composing! Keep composing!’”