New York City's Brick River

In the 19th century, New York City residents got their

drinking water from sidewalk pumps like this one. Initially, the

water was so pure that the dispensers were called "tea-water"

pumps.

In the 19th century, New York City residents got their

drinking water from sidewalk pumps like this one. Initially, the

water was so pure that the dispensers were called "tea-water"

pumps. In the early 1800s, residents of

New York City got their drinking water from sidewalk pumps that

tapped into the city’s aquifer. But as industry in the city grew,

the water became contaminated with the runoff from breweries,

tanneries, slaughterhouses, and waste (both livestock and human).

The city fathers recognized that, if the metropolis were to

flourish, it needed a dependable source of clean water. Two

seminal events spurred them to action: the cholera epidemic of

1832, during which the water-borne bacteria killed 3,515

residents, and the Great Fire of 1835, which burned for three days

and destroyed 17 city blocks in part because of a lack of readily

available water.

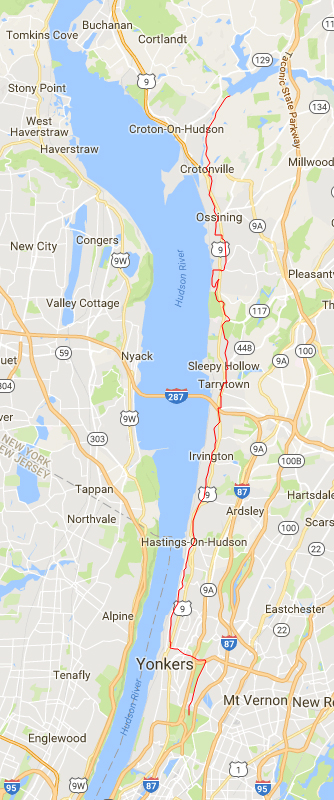

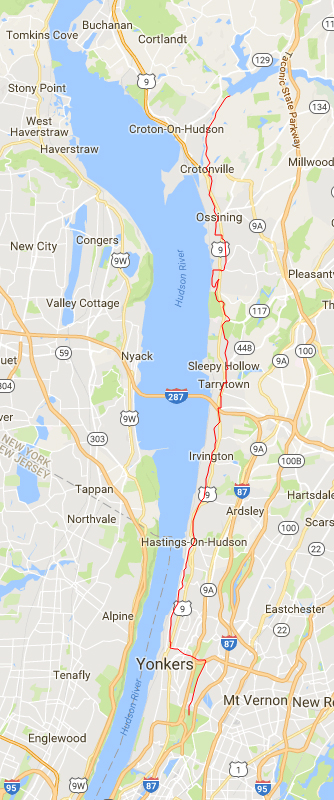

It took from 1837 to 1842

to build the 41-mile Croton Aqueduct.

It took from 1837 to 1842

to build the 41-mile Croton Aqueduct.

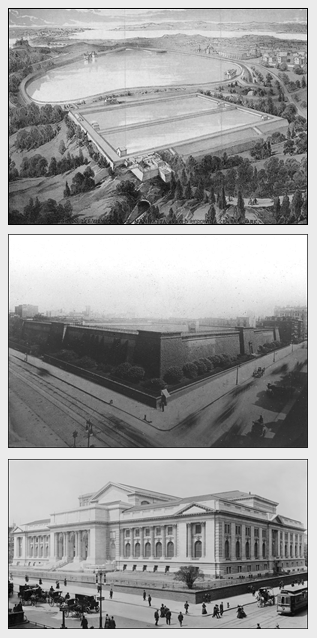

Top: The receiving

reservoir in Central Park, now the location of the Great Lawn.

Top: The receiving

reservoir in Central Park, now the location of the Great Lawn.

Middle: The distributing reservoir at 5th Avenue (left) and 42nd

St. (right). It was a massive affair that held 20 million

gallons of water and had a promenade along the top, popular with

residents for Sunday afternoon strolls.

Bottom: In the late 1890s, the midtown reservoir was torn down

to make way for the New York Public Library's main branch. This

image was taken before the installation of Patience and

Fortitude, the two marble lions that guard the library's

entrance.

Photos © New York Public Library.

As a result, in 1837, work began on one of the most ambitious

municipal projects of the era: an aqueduct that would bring water

from the pristine Croton River 41 miles north of Manhattan into the

city. Once there, the water would be stored in two reservoirs, a

receiving reservoir in Central Park, and a distributing reservoir on

42nd St.

By any account, the aqueduct was an impressive feat of engineering.

It was built of bricks and hydraulic cement, the latter being

especially resistant to wet environments. It used no mechanical

pumps—water flowed to the city by the force of gravity alone. To

accomplish that, the aqueduct dropped 13 inches every mile.

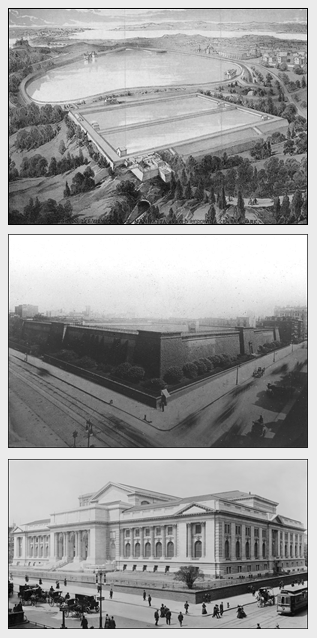

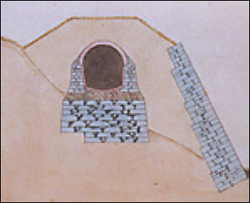

The aqueduct is buried

throughout its 41-mile length.

The aqueduct is buried

throughout its 41-mile length.  Today, the aqueduct is a

public trail, but you can still see its rounded earth covering.

Today, the aqueduct is a

public trail, but you can still see its rounded earth covering.

Photo © ScubaBear68 via Flickr.

To meet that precise requirement, the horseshoe-shaped brick

tunnel was secured on a stone foundation and topped by a dirt

berm. The berm's telltale round top still marks the path of the

aqueduct today.

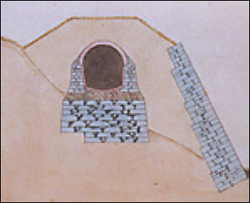

Beautiful stone

ventilators prevented a vacuum from forming inside the aqueduct.

Beautiful stone

ventilators prevented a vacuum from forming inside the aqueduct.

Photos © school 1106 via panoramio.

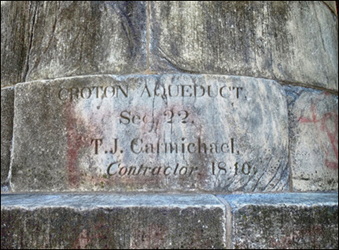

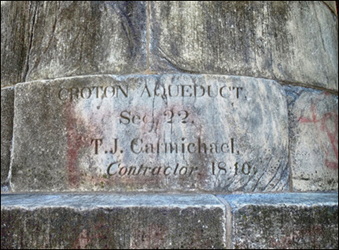

Ventilator shafts were

sometimes inscribed with the section number of the aqueduct and

signed by the builder, like this inscription from ventilator 8

in Ossining, NY.

Ventilator shafts were

sometimes inscribed with the section number of the aqueduct and

signed by the builder, like this inscription from ventilator 8

in Ossining, NY.

Photos © Carlos Gee.The

aqueduct was far more than a giant brick sluice, however. To prevent

a vacuum from forming inside it as water rushed downstream, 33

above-ground ventilators—giant stone “breather” tubes—were built

about every mile.

The tunnel sent up to 90 million gallons of water to the city

each day, and it needed regular care.

The weir in Ossining, NY.

The weir in Ossining, NY.

Photo © Peter McKie.

A view inside the

Ossining weir. Turning the wheel in the left photo lowered the

giant steel gate in the top right photo, preventing water from

entering the aqueduct, and diverting the flow to a nearby river

via a side pipe (bottom right).

A view inside the

Ossining weir. Turning the wheel in the left photo lowered the

giant steel gate in the top right photo, preventing water from

entering the aqueduct, and diverting the flow to a nearby river

via a side pipe (bottom right).

Photos © Peter McKie.

To inspect, maintain, and repair the tunnel, caretakers had to empty

the aqueduct. To that end, six stone structures, called weirs, were

built along the conduit. They housed giant metal gates that, when

closed, shunted the water in the aqueduct to nearby rivers. One of

those weirs, in Ossining, NY, is open to the public a few times a

year (go

here for a tour schedule).

The keeper's house in

Dobb's Ferry, NY, deteriorated over time. In 2001, a citizen's

group cobbled together the money to save it.

The keeper's house in

Dobb's Ferry, NY, deteriorated over time. In 2001, a citizen's

group cobbled together the money to save it.

Photos © Friends of the Old Croton

Aqueduct. Each weir required

a caretaker, who was given the use of a “keeper’s house” near their

secton of the aqueduct. Of the six houses built, only the one in

Dobbs Ferry, NY, remains in its original location. In 2001, that

rundown structure, built in 1857, was fully restored. It now serves

as the aqueduct's museum.

The recently discovered

(2014) keeper's house in Ossining, NY.

The recently discovered

(2014) keeper's house in Ossining, NY.

Photo © Ossining Historical

Society. Until recently, the

Dobb's Ferry building was thought to be the only remaining keeper's

house. In 2014, however, a second house, in Ossining, NY, was

identified and confirmed. It turns out that in 1928, the house was

moved from its location next to the aqueduct to a residential

street, where it is now a private home.

Inside the High Bridge,

the aqueduct water is carried by a giant pipe. Note that the

pipe is held together by rivets, an indicator of how old it is;

today, welds would replace the rivets.

Inside the High Bridge,

the aqueduct water is carried by a giant pipe. Note that the

pipe is held together by rivets, an indicator of how old it is;

today, welds would replace the rivets.

Photo © shayna

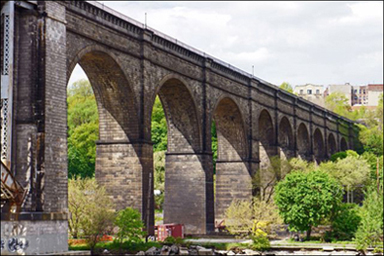

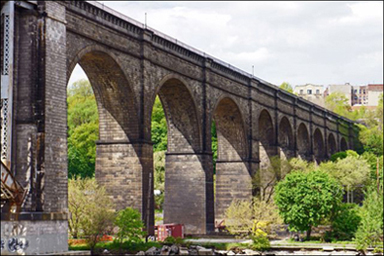

Despite the distance the Croton water had to travel, only three

bridges had to be built to span obstructions. The most noteworthy

was the High Bridge, built in 1848 and modeled after the Roman

aqueducts. It stretches 1/4 mile over the Harlem River in northern

Manhattan.

The High Bridge rises 140

feet above the Harlem River.

The High Bridge rises 140

feet above the Harlem River.

Photo © H.I.L.T. via Flickr

The original aqueduct dam

on the Croton River, in Croton-on-Hudson, NY.

The original aqueduct dam

on the Croton River, in Croton-on-Hudson, NY.

Photo © Museum of the City of New

York.  In

1906, a new, higher dam was built to meet the increased demand

for water. Its design includes a flashy spillway, part natural

(left) and part manmade (right), that complements the land below

the dam, which has been turned into a state park.

In

1906, a new, higher dam was built to meet the increased demand

for water. Its design includes a flashy spillway, part natural

(left) and part manmade (right), that complements the land below

the dam, which has been turned into a state park.

The new dam sits slightly to the south of the old one, and in

times of drought, you can see the remnants of old dam under

the water.

Photo © John via Flickr.

The aqueduct cost $13 million to build and took 5 years to complete.

Irish immigrants provided most of the labor at the rate of $1 a day.

The aqueduct trail goes

through Lyndhurst, tycoon Jay Gould's 67-acre estate overlooking

the Hudson River. The mansion is open to the public.

The aqueduct trail goes

through Lyndhurst, tycoon Jay Gould's 67-acre estate overlooking

the Hudson River. The mansion is open to the public.

Photo © National Trust for Historic

Preservation. In 1968, New

York State bought 26.2 miles of the aqueduct and opened it to the

public as the Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park. The flat

trail atop the aqueduct is ideal for walking, biking, and

cross-country skiing.

The trail winds through commercial areas; residential areas

(including people's back yards via easements still in place); the

grounds of Lyndhurst, railroad tycoon Jay Gould's riverside

mansion; and along the path of many old Hudson River estates.

While modern development means that the aquduct is no longer a

contiguous 41 miles, trail maps show workarounds for inaccessible

areas.