Nazi Sub Found in New Jersey

Nagle's

boat Seeker served as home base for

deep-wreck divers.

Nagle's

boat Seeker served as home base for

deep-wreck divers.

Photo © John Chatterton.

In 1985, Nagle's dive

team found the Andrea Doria's stern bell.

In 1985, Nagle's dive

team found the Andrea Doria's stern bell.

Photo © Mike Boring.

In 1991, a retired longtime deep-wreck diver named Bill Nagle, who led

a team that recovered one of the Andrea Doria's ship's bells,

was captain of the recreational deep-dive boat Seeker out of

New Jersey.

Nagle heard an intriguing tale from a friend and local charter-boat

captain: Every time the captain took a group out to an area off the

coast, all his clients caught fish. The captain knew that that was

no fluke, and told Nagle "there's something under there.”

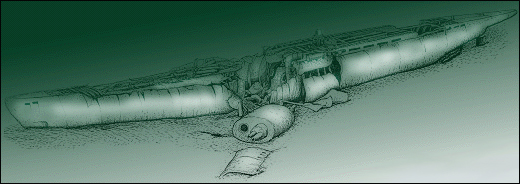

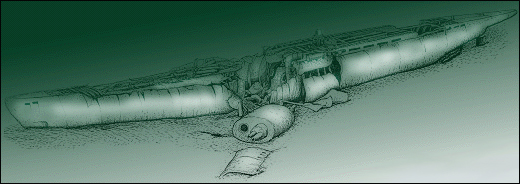

The sub as the divers found

it; its conning tower had sheered off, exposing the U-boat's

interior.

The sub as the divers found

it; its conning tower had sheered off, exposing the U-boat's

interior.

Sketch © Dan Crowell.

Curiosity got the best of Nagle, and he and some diver buddies,

including John Chatterton and Richie Kohler, organized an expedition

to the area. Sure enough, just 60 miles off the coast of New Jersey,

they found the wreck of a World War II German submarine. When the

divers checked Navy records, they found that no wreck had been

recorded for that position. That began a six-year adventure to

identify the U-boat and its crew.

This is what the inside of

the wreck looked like on dives.

This is what the inside of

the wreck looked like on dives.

Still from Shadow Diver video © John Chatterton.

The explorers searched the sub for a hull or boat number that would

positively identify the wreck. Their dives were fraught with

danger—the sub sat in 240 feet of water (130 feet is considered a

safe deep dive), required 250 pounds of gear, decompression stops on

the way up, and scuba tanks full of a mixture of three gasses for

faster decompression. Over the course of the six-year journey, three

divers lost their lives.

Even with all that equipment, the divers could stay at the bottom

for only 30 minutes at a time. To make matters worse, the sub was

badly damaged—-to find anything that identified the sub, the divers

had to navigate a mass of cables, dislodged equipment, and sediment.

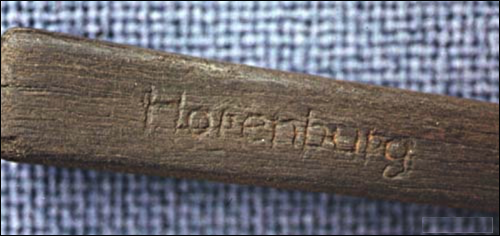

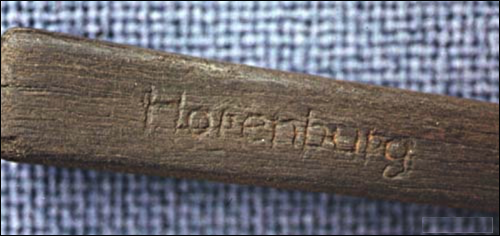

The first clue to the sub's

identity was this dinner knife, inscribed with a crew member's

name.

The first clue to the sub's

identity was this dinner knife, inscribed with a crew member's

name.

Photo © Richie Kohler.

Full view of knife.

Full view of knife.

Photo © Richie Kohler.

The first clue to the boat’s identity came from an unlikely source—a

dinner knife. It had the name "Horenburg" scratched into the handle.

The divers flew to Germany to research U-boat manifests and found that

a radio operator named Martin Horenburg had been assigned to sub

U-869. But the records also showed that U-869 sank off the coast of

Gibralter, not New Jersey. Furthermore, Horenburg served on several

U-boats, and could have left the knife on any one of them. They were

back to square one.

During the off-season, the divers researched the history of

U-boats. They learned that, at the start of a patrol, spare parts

were loaded into boxes and then onto the subs. Those boxes had tags

that identified the U-boat the parts were destined for. The divers

decided to look for those tags on subsequent dives.

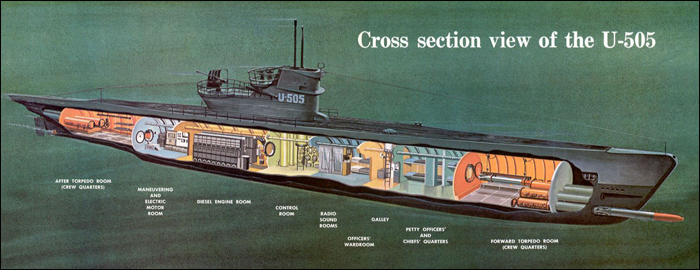

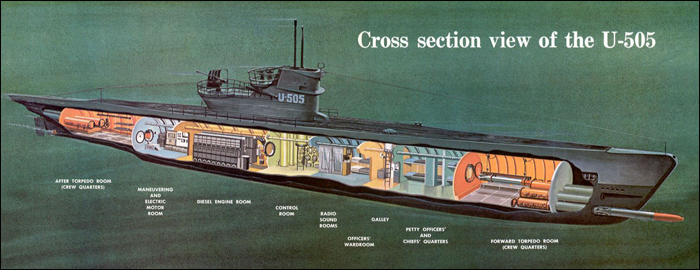

This cross-section of

U-505, a twin of U-869, shows the aft part of the sub that the

divers hadn't been able to explore because of a fallen fuel tank

(click image for an enlarged view). It included the diesel motor

room (used when surface cruising), the electric motor room (used

when submerged), and the aft torpedo room.

This cross-section of

U-505, a twin of U-869, shows the aft part of the sub that the

divers hadn't been able to explore because of a fallen fuel tank

(click image for an enlarged view). It included the diesel motor

room (used when surface cruising), the electric motor room (used

when submerged), and the aft torpedo room.

Illustration © Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago.

Up to that time, the divers had been able to explore all but the rear

of the sub—the location of the diesel and electric motor rooms, and

the aft torpedo room.

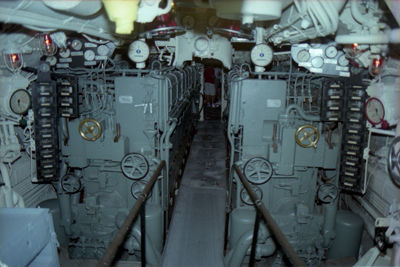

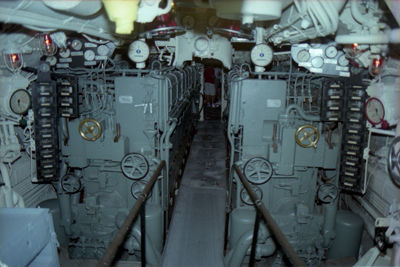

This is the diesel room on

the wreck. The engines sit on the left and right. Wedged between

them and blocking the divers' way is the oil tank that fell from

the ceiling. Chatterton went through the hole above the tank.

This is the diesel room on

the wreck. The engines sit on the left and right. Wedged between

them and blocking the divers' way is the oil tank that fell from

the ceiling. Chatterton went through the hole above the tank.

Photo © Richie Kohler.

A large oil tank, which fed the diesel engines and was normally bolted

to the ceiling, had fallen and blocked the path to those rooms. The

area below the tank was too small for a diver to get through, and the

area above it was too restricted for a diver and his gear. Their

solution? One of the divers, Chatterton, would take off his air tanks

and guide one of them into the larger, topmost space. He’d follow, and

reattach the tank on the other side. At a depth that even the Navy

considers sketchy, and with the wreck already having claimed three

lives, it was a dangerous maneuver.

This is what the two power

plants in the diesel engine room originally looked like.

This is what the two power

plants in the diesel engine room originally looked like.

Photo © Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago.

Chatterton's first try was unsuccessful—he got through the hole all

right, but once inside, he kicked loose a pipe that landed on him.

It took his entire bottom time to extricate himself. The next day,

he made it past the obstruction, through the diesel room, and into

the electric motor room. There, near a fuse panel, Chatterton saw

boxes of spare parts. He grabbed one, handed it to dive buddy Kohler

back in the diesel room, and they surfaced.

The Rosetta Stone of the

U-869. This box of spare parts held the key to the sub's identity.

The Rosetta Stone of the

U-869. This box of spare parts held the key to the sub's identity.

Photo © John Chatterton.

Back up on deck, the divers found what they'd spent six years looking

for—an identifying plate attached to the parts box. It read "U-869."

The divers finally knew the identity of the long-lost sub.

Close-up of the tag that

identified U-869. "Hauptlenzpump" translates to "main pump."

Close-up of the tag that

identified U-869. "Hauptlenzpump" translates to "main pump."

Photo © John Chatterton.

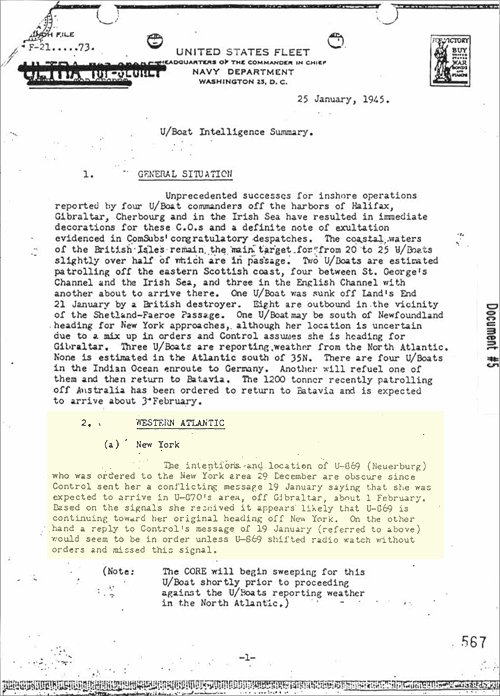

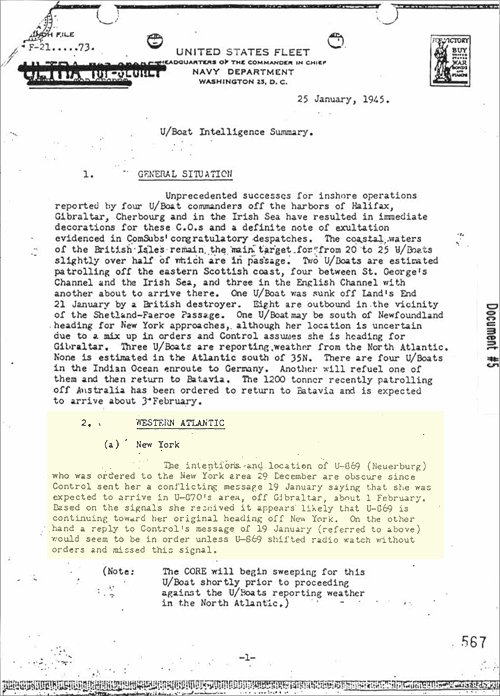

This is the Allied

surveillance report noting that U-869 had not followed orders to

change course for Gibralter. Click image to enlarge tinted area.

This is the Allied

surveillance report noting that U-869 had not followed orders to

change course for Gibralter. Click image to enlarge tinted area.

Document © U.S. Navy and John Chatterton.

So how did U-869 end up off the coast of New Jersey, and how had it

met its end?

That's where the divers and the Navy disagree. The divers felt that

U-869 had been practice-firing its torpedoes when one of the

munitions doubled back and struck the sub—torpedoes of that era

homed in on high-speed propeller noises, and in the absence of a

true moving target, the torpedo targeted U-869 itself, they

theorized.

But the Navy believes otherwise. According to Allied surveillance,

on December 29, 1944, Germany's U-Boat Command Center gave U-869 and

its crew of 56 its first—and last—orders: to patrol New York Harbor.

U-869 radioed back, acknowledging the order.

Some time after that, the Command Center worried that U-869 was

running low on fuel and redirected it to the coast of Gibraltar. But

U-869 never received those orders and continued on its way to the

east coast.

On February 11, 1945, two U.S. warships were returning to New York

Harbor when they detected a sub on their sonar. The first boat

launched underwater mortars, while the second deployed depth

charges. A few minutes later, both crews saw the signs of a hit—oil

slicks on the ocean's surface and air bubbles rising from the

depths. Sonar readings confirmed that the sub had stopped moving.

U-869 wasn't seen for the next 60 years.

The telegraph (engine speed

control) as found on the wreck of U-869 (left) and an intact

telegraph on twin sub U-505 (right).

The telegraph (engine speed

control) as found on the wreck of U-869 (left) and an intact

telegraph on twin sub U-505 (right).

Photo © Richie Kohler (left) and Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago

(right). In addition to

Horenburg’s dinner knife (which the divers returned to his

descendants), artifacts recovered from U-869 include mechanical

equipment, dinnerware stamped with the emblem of the Third Reich,

medical supplies, and engine tags.

All the dinnerware on U-869

was stamped with the Parteiadler--the eagle-and-swastika emblem of

the Nazi Party.

All the dinnerware on U-869

was stamped with the Parteiadler--the eagle-and-swastika emblem of

the Nazi Party.

Photo © Richie Kohler.

Medical supplies.

Medical supplies.

Photo © Richie Kohler.

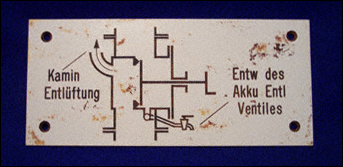

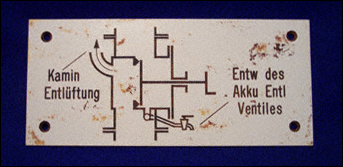

Machine plate. The left

label reads ""Fireplace ventilation," and the right one reads

"Battery drain valve." If a sub submerged at too steep an angle,

acid from the electric motor batteries could leak out.

Machine plate. The left

label reads ""Fireplace ventilation," and the right one reads

"Battery drain valve." If a sub submerged at too steep an angle,

acid from the electric motor batteries could leak out.

Photo © Richie Kohler.

The divers returned to the wreck one more time, on August 5, 2001,

to lay a memorial wreath. Diver Richie Kohler read this eulogy:

"This morning we gather here to remember the 56 fallen men of the

submarine U-869, and to honor the wishes of their families, friends,

and loved ones. We also remember the three divers who have died here

as well. We have come to mourn their loss and celebrate their lives.

We bring with us this wreath in memory of their lives and the lives

they have touched, and this ribbon in recognition of their service

and sacrifice to their countrymen."